RYCEF

0.5300

The theory of quantum mechanics has transformed daily life since being proposed a century ago, yet how it works remains a mystery -- and physicists are deeply divided about what is actually going on, a survey in the journal Nature said Wednesday.

"Shut up and calculate!" is a famous quote in quantum physics that illustrates the frustration of scientists struggling to unravel one of the world's great paradoxes.

For the last century, equations based on quantum mechanics have consistently and accurately described the behaviour of extremely small objects.

However, no one knows what is happening in the physical reality behind the mathematics.

The problem started at the turn of the 20th century, when scientists realised that the classical principles of physics did not apply to things on the level on atoms.

Bafflingly, photons and electrons appear to behave like both particles and waves. They can also be in different positions simultaneously -- and have different speeds or levels of energy.

In 1925, Austrian physicist Erwin Schroedinger and Germany's Werner Heisenberg developed a set of complex mathematical tools that describe quantum mechanics using probabilities.

This "wave function" made it possible to predict the results of measurements of a particle.

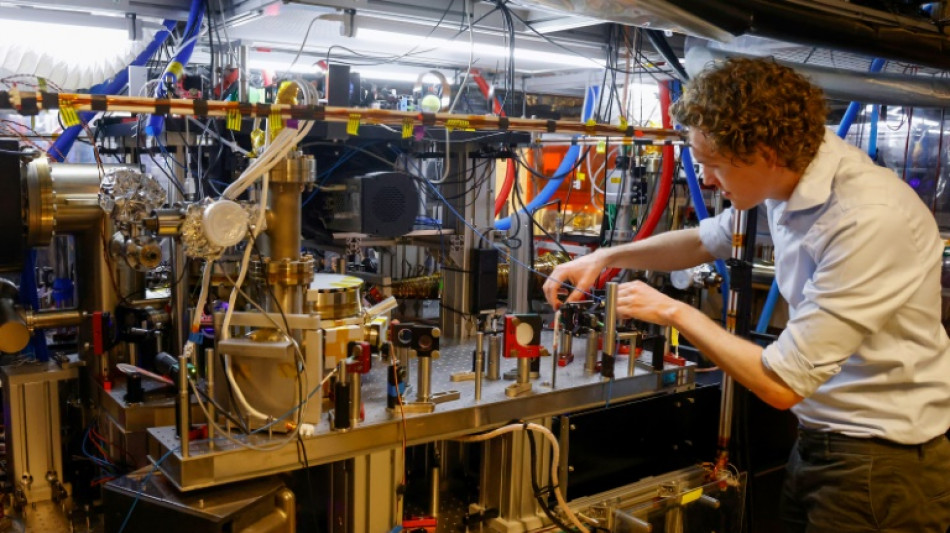

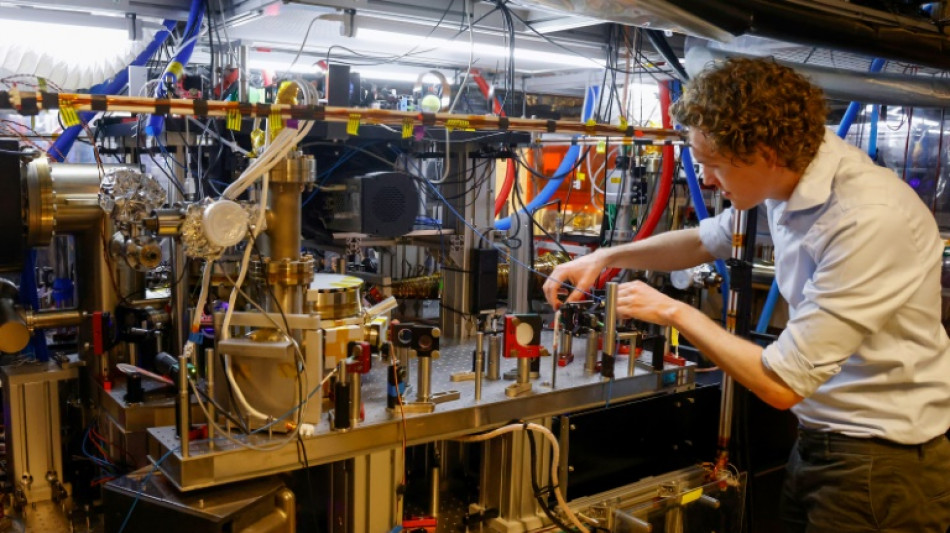

These equations led to the development of a huge amount of modern technology, including lasers, LED lights, MRI scanners and the transistors used in computers and phones.

But the question remained: what exactly is happening in the world beyond the maths?

- A confusing cat -

To mark the 100th year of quantum mechanics, many of the world's leading physicists gathered last month on the German island of Heligoland, where Heisenberg wrote his famous equation.

More than 1,100 of them responded to a survey conducted by the leading scientific journal Nature.

The results showed there is a "striking lack of consensus among physicists about what quantum theory says about reality", Nature said in a statement.

More than a third -- 36 percent -- of the respondents favoured the mostly widely accepted theory, known as the Copenhagen interpretation.

In the classical world, everything has defined properties -- such as position or speed -- whether we observe them or not.

But this is not the case in the quantum realm, according to the Copenhagen interpretation developed by Heisenberg and Danish physicist Niels Bohr in the 1920s.

It is only when an observer measures a quantum object that it settles on a specific state from the possible options, goes the theory. This is described as its wave function "collapsing" into a single possibility.

The most famous depiction of this idea is Schroedinger's cat, which remains simultaneously alive and dead in a box -- until someone peeks inside.

The Copenhagen interpretation "is the simplest we have", Brazilian physics philosopher Decio Krause told Nature after responding to the survey.

Despite the theory's problems -- such as not explaining why measurement has this effect -- the alternatives "present other problems which, to me, are worse," he said.

- Enter the multiverse -

But the majority of the physicists supported other ideas.

Fifteen percent of the respondents opted for the "many worlds" interpretation, one of several theories in physics that propose we live in a multiverse.

It asserts that the wave function does not collapse, but instead branches off into as many universes as there are possible outcomes.

So when an observer measures a particle, they get the position for their world -- but it is in all other possible positions across many parallel universes.

"It requires a dramatic readjustment of our intuitions about the world, but to me that's just what we should expect from a fundamental theory of reality," US theoretical physicist Sean Carroll said in the survey.

The quantum experts were split on other big questions facing the field.

Is there some kind of boundary between the quantum and classical worlds, where the laws of physics suddenly change?

Forty-five percent of the physicists responded yes to this question -- and the exact same percentage responded no.

Just 24 percent said they were confident the quantum interpretation they chose was correct.

And three quarters believed that it will be replaced by a more comprehensive theory one day.

U.Chen--ThChM