SCS

0.0200

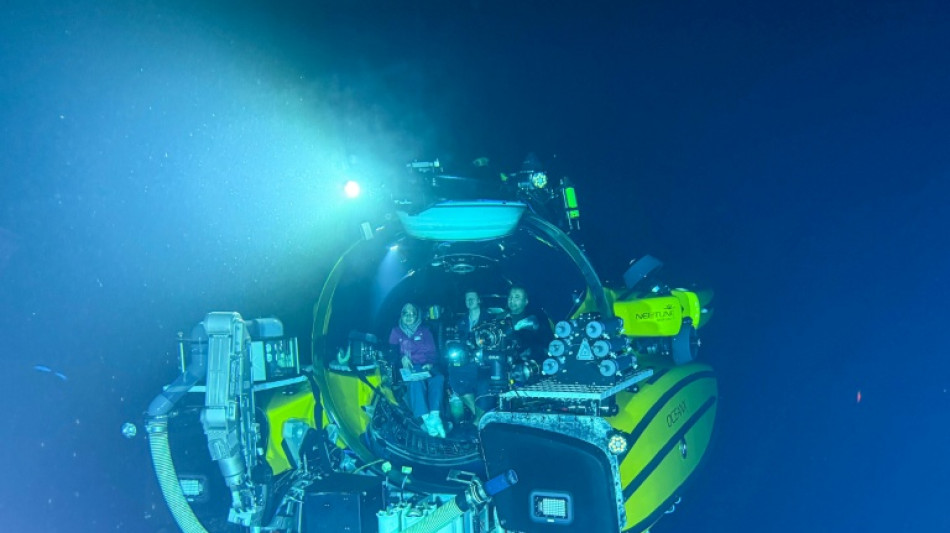

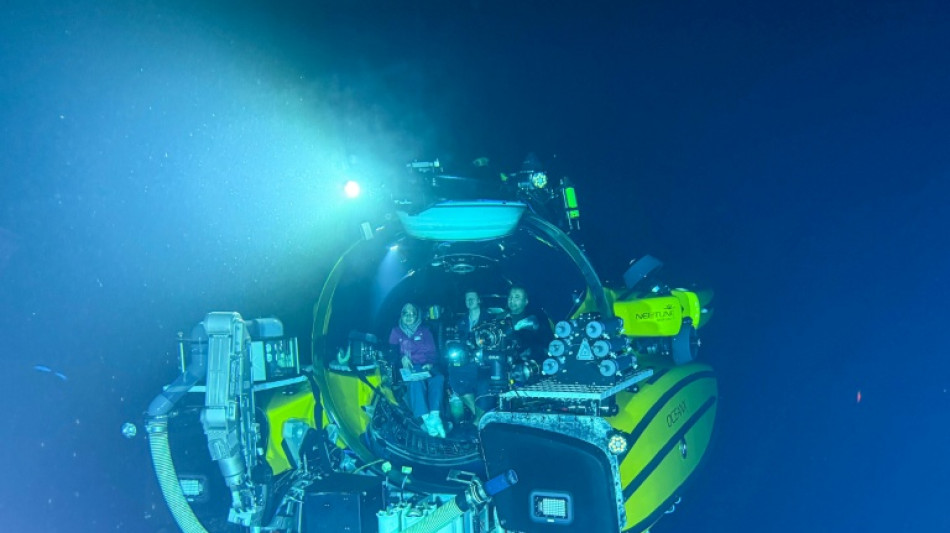

A dome-fronted submersible sinks beneath the waves off Indonesia, heading down nearly 1,000 metres in search of new species, plastic-eating microbes and compounds that could one day make medicines.

This month, AFP boarded one of two submersibles belonging to OceanX, a non-profit backed by billionaire Ray Dalio and his son that brings scientists onto its OceanXplorer ship to study the marine world.

The ship boasts labs for genetic sequencing, a helicopter for aerial surveys and a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) capable of descending up to 6,000 metres (19,700 feet) under the ocean surface.

Its two submersibles have everything from hydraulic collection arms and suction tubes to high-definition cameras, allowing them to uncover the improbable life found in some of the harshest conditions on Earth.

The ship's latest mission focuses on a seamount chain off Indonesia's Sulawesi island that scientists on board mapped last year.

A new team of Indonesian scientists is now surveying its biodiversity, including with submersible dives that put the researchers right into the environment they are studying.

As the sub dropped below 200 metres, the last traces of light disappeared, and indigo faded into total darkness.

Husna Nugrahapraja, an Indonesian scientist on the mission, admitted feeling "a little bit nervous and anxious" as he descended on his first submersible trip.

It is a "very lonely" environment at first, the assistant professor at Institut Teknologi Bandung told AFP.

The craft's lights offered the only illumination, revealing drifts of "marine snow" -- a shower of debris, including decomposing animals, that falls continuously into the depths and creates the impression of an old television stuck between stations.

Marine life that most people never see floated into view, including delicate comb jellies with pulsing fairy-light illuminations along their sides.

Siphonophores -- largely translucent creatures in fanciful shapes resembling toddlers' drawings -- glowed as they drifted by, and silver, fingernail-sized fish skittered out of the sub's wake.

Finally, Husna said, "we arrive on the sea bed... (where) we can see many unique organisms", from delicate sea stars to fronded soft corals.

- 'Quite different' -

OceanXplorer's Neptune submersible is designed for scientific collection and observation, while its Nadir vessel has high-end cameras and lights for media content.

That reflects OceanX's view that compelling images make research more accessible and impactful.

The subs do not go as deep as an ROV, but offer a unique view, explainedDave Pollock, who heads OceanX's submersible team.

"We get a lot of scientists come on who are very sceptical about subs," he told AFP.

"Pretty much without fail every sceptical scientist that comes on board who gets to go on a dive changes their opinion."

The nearly 360-degree view gives them "a totally different perspective" to the flat video fed up to the ship by the ROV.

"It's quite different when you see it yourself," Husna said.

The submersibles also offer unique experiences, including the flashes of light called bioluminescence that many deep-sea animals produce to communicate, for defence, or to attract mates.

The vessel's powerful light beams can be used to elicit the display.

First, all the lights are switched off. Even the internal control board is covered, plunging the craft's occupants into total darkness.

Then the sub flashes its lights several times while those on board close their eyes.

When they open them, a seascape galaxy of stars appears -- the bluish-white flashes of creatures from plankton and jellyfish to shrimp and fish responding to the sub lights.

Pollock, who has spent hundreds of hours diving in submersibles, counts some of the more spectacular "flashback bioluminescence" events as among the most memorable moments in his career.

Submersibles are used in many fields, but many now associate them with the 2023 underwater implosion of the Titan, which killed five people on a trip to explore the Titanic wreck.

Pollock stressed that, unlike Titan, OceanXplorer's vehicles are designed, manufactured and inspected regularly in accordance with industry body DNV.

"The subs are designed safe" and equipped with back-up systems including four days of emergency life support, he said.

- 'So little we know' -

For deeper exploration, the scientists rely on OceanX's ROV, operated from a futuristic-looking "mission control" where two crew members sit in gamer-style armchairs.

A bank of screens shows the largely barren seabed, as an operator uses a multi-jointed joystick to operate the robot's hydraulic arm from thousands of metres above.

It resembles a space mission, with an intrepid rover traversing desolate distant terrain. But here there are aliens.

At least that is how some of the species encountered appear to the untrained eye.

There's a bone-white lobster, suctioned up for examination at the surface, and a horned sea cucumber whose mast-like spikes collapse into black spaghetti when it arrives on the ship.

And there's a deep-sea hermit crab, living not inside a shell, but a sea star the team can't immediately identify. The crab has laid lurid orange eggs inside its long-dead host.

Not every collection is a success: a delicate red-orange shrimp daintily eludes the suction tube, swirling its long antenna as it swims almost triumphantly beyond reach.

When the ROV returns, there is an excited dash for the samples including seawater, sediment and a forearm-length sea lily coated with dripping orange goo.

Crustacean specialist Pipit Pitriana from Indonesia's National Research and Innovation Agency is fascinated by the captured lobster, as well as some pearl-sized barnacles she thinks may be new to science.

Large parts of the ocean, particularly the deep sea floor, are not even mapped, let alone explored.

And while a new treaty to protect international waters entered into force this month, the ocean faces threats from plastic pollution and rising temperatures to acidification.

"Our Earth, our sea, is mostly deep sea," Pipit said.

"But... there is so little we know about the biodiversity of the deep sea."

Q.Moore--ThChM